A I D I A

A Venture of Enacting Meaningful Resistance Within the Content of a Ukiyo-e Courtesan Print

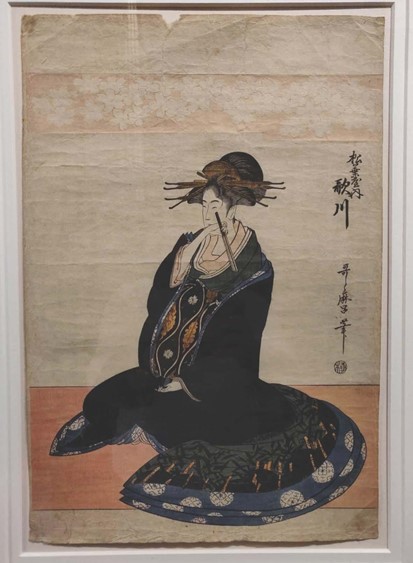

This work by Utamaro depicts a lovely courtesan, an embodiment of the tastes of Edo in the 19th century. Edo was a bustling city with a majority male population who were away from their homes for six months out of the year on the Daimyo’s orders. Edo was the city where all politicians gathered for court, and as we see today, where there is politics there is money. Merchants from the Edo period picked up on this new money trail and followed the scent, making many new brothels, theaters, restaurants, and wares in the Yoshiwara district (literally meaning woman of pleasure in Japanese). The courtesans within the district began to increase in fame due to a new artistic genre of the time called Ukiyo-e: highly colorful wood block prints depicting a range of subjects from landscapes to famous theater actors. One of the most popular trends was bijin-ga, where the most beautiful and sought-after courtesans would be portrayed to encourage visitation of the Yoshiwara district, but also to appeal to a male-dominant society who had newfound buying power due to Japan’s long period of peace. The Yoshiwara district, the setting for a lot of bijin-ga, was crafted to quell all the desires a man could ever have from sex, to hunger, to amusement, too often relegating women to being objects a man could gain profit from. Kitagawa Utamaro’s work Courtesan Seated Holding a Fan embodies the Yoshiwara district’s elaborate male-dominant system of using women as a tool to gain personal, physical, and visual pleasure. However, despite men’s attempts to objectify and commodify women, meaningful resistance to these dominating trends forms in the interpretations of people (especially women) now.

She wears a richly colored kimono with nightly blues and aged yellow accents. This color combination is classic, yet effective. The base of her dress forms a spiral from the foreground towards the dark blues which nestle her body drawing our eyes up the composition; the blues are heavily contrasted against the yellows at her neckline, and her pure white face is slightly obscured by her right hand holding a fan. Viewers of the time would have noticed, when looking over her kimono, the loosened neckline. This would have been quite suggestive at the time as the neck was a highly desired place on a woman’s body. The fan’s slight covering of her face does little to hide her beauty, in fact, it almost taunts viewers into more admiration. This slight unravelling of her kimono (seen by the bent crease at the top rather than a straight fold) combined with the smallest of obscuration of her neck is playing with a male audience’s desires. When something is just ever so slightly covered, people often even more desperately want to experience the whole thing. This is even more frustrating for viewers as they cannot get another view of the courtesan as this is a print, an unchanging object. Utamaro is clearly nudging viewers to be desirous of this courtesan in order to encourage the continued adoration of the Yoshiwara district so he and many other men can continue to profit from these women’s bodies and beauty.

Another effective compositional device is the breaking up of the background into roughly three sections: the orange carpet and below, the central large white expanse, and the flower border and above. These oranges nicely compliment the blue tones within the image and the flower border at the top references the abundance of sexual and visual titillation the courtesan presents. Her jet-black hair with what would have been tortoise shell combs arranged in a popular style of the time called yoko-hyogo, or butterfly. These “wings” which extend out beside her head evoke the wings of a butterfly, but to me, also look similar to the sun-shaped haniwa from the Kofun Period or the wings on the main hall of the Ise Shrine. These wings of her hair would also have extended to about the length of her figure, which was seen as an attractive expression, referencing the other part of the courtesan’s stature. This hairstyle also gave viewers greater visual access to the courtesan’s neck.

The series as a whole depicts courtesans from the Matsubaya brothel, one notorious for exceptionally beautiful women. Both Utamaro, the brothel, viewers of the time, bijin-ga, and the Yoshiwara district rely on the objectification of women’s bodies to elicit pleasure from men in order to gain wealth. The creation of the woodblock print, which saw only men carving the block, deciding what is good enough to publish, and executing all of the intermediary steps of printing, in order to create the best product and sell the most copies. Within the Yoshiwara district, brothels would buy young girls from impoverished families at the ages of 7 or 8. These purchases would often be under a ten-year contract that the children had to work off in order to gain back autonomy. However, if a courtesan were to require kimonos or personal items the brothel would add that cost to their contract, meaning that as one became a more and more distinguished courtesan, their debts would increase and increase, meaning gaining freedom was incredibly unlikely1. This use of women for men’s personal gain was a frequent occurrence at the time, making finding resistance to these dominant marginalizing structures hard to find within the period. In the present day, women can find great meaning in the depiction of these courtesan women who led meaningful lives full of creation. They were mothers, laborers, and people whose mere existence should be celebrated for their contribution to Japanese society, despite it not being depicted on their terms or too often overlooked. Present day women and I can choose to interpret the brightly colored works of bijin-ga as adoration or celebration of these women’s beauty, musical skill, and fashion, however, to do so risks ignoring the harsh realities these women often faced within the period. Centering the marginalization these women faced and acknowledging the active use of women for profit by men of the Edo period is vital before making a celebratory interpretation of the work. However, to continue to just understand these women as victims of men’s whims and schemes for profit also renders them as less than human, or objects of marginalization, not women who had lives full of meaning and creation. This makes reparative interpretations vital to continued engagement with these works:

The courtesan patiently sits in her room after a long night of work, just having grabbed her fan in order to cool off on this hot night. Her kimono embodies the turbulent night winds that come in the summer. The flower pattern at the bottom evokes the clear night’s radiant moonlight, with the gold accents on her chest reflecting the lanterns lighting the space. Her friends are soon headed to her room for a late-night tea to discuss the daily ups and downs and news obtained from clients and outings. Her friends, displayed in the pages adjacent to these, all are excellent musicians, and their friend group gathers around this courtesan’s duplicitously delicate voice: quiet and meandering, yet —at just the right moment— full-bodied in its emotion, often at the peak of a given piece. The background which she sits against is full of creamy oranges, alluding to the coming dawn and the blossoming of the sun’s rays over their harem. This juxtaposition of the background’s orange against her kimonos blues pushes her forward in space, celebrating her beauty, her wondrous voice, delightful person, and valuable friendships.